Voices From The Ground: How COVID-19 has Affected Homeworkers in South Asia’s Garment Supply Chains

The COVID-19 outbreak has impacted global garment supply chains causing brands and retailers to close shops and cancel orders from sourcing factories. This has resulted in mass layoffs and has had a devastating effect on the livelihoods of homeworkers – who form the lowest tiers of supply chains.

To gain perspectives on this issue, HomeNet South Asia (HNSA) along with WIEGO hosted a webinar titled COVID-19: Homeworkers Working for Global Brands, South Asia Perspective. The webinar was conducted as part of the DFID WoW Webinar and Exchange Series and took place on June 11, 2020. Home-based worker organisations and leaders from four countries took part in the webinar. Participating organisations included SABAH Nepal, SAVE (Tiruppur, India), SEWA Bharat (West Bengal, India), Labour at Informal Economy (LIE) from Bangladesh, and Home Based Women Workers Federation (HBWWF) from Pakistan. The webinar was aimed at understanding the challenges faced by homeworkers in garment supply chains as well as by their representative organisations, their short-term and long-term responses to the COVID-19 crises and their future actions.

Challenges Faced

Food insecurity, financial crises, and the loss of livelihoods are the main challenges faced by homeworkers, in South Asia, after governments across the region, imposed lockdowns in late March 2020. Government-backed relief programmes have been poorly implemented and have been limited to the distribution of food rations that feed families for a few days. These food programmes are also only applicable to those with the necessary paperwork – leaving out huge swathes of the population especially migrant workers.

Additionally, workers are struggling to pay home rents and to sustain their day-to-day needs. Here, South Asian governments have fallen short in extending the necessary social security nets that protect vulnerable homeworkers and their families. This has driven many to take up loans with little means to repay them.

When it comes to their livelihood, homeworkers in garment supply chains find that they are strapped with stockpile because goods aren’t moving and markets are closed. On the other hand, they also lack access to raw materials and working capital to sustain their work. Members of collectives and organisations like SABAH Nepal, SEWA Bharat, LIE and HBWWF have been able to access income opportunities as these organisations have realigned their supply chains to produce Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for frontline workers. However, these initiatives are still in their nascent stage and orders are not large enough to provide work to a large number of homeworkers.

While lockdowns are easing, across the region, work is scarce and homeworkers in garment supply chains fear that orders will remain on the lower end for the rest of 2020. Evidence of the scarcity of work is already unfolding in many garment hubs. In Tiruppur, for example, while the lockdown has been lifted, only 25% of the 5000-odd homeworkers registered with SAVE have been able to access work at severely reduced piece-rates.

Addressing The Impact

Where governments have fallen short, organisations of homeworkers have worked to fill the gap. HBW organisations have been working tirelessly to help members and families survive the fallouts of the pandemic by extending food support, trainings, conducting awareness campaigns, and are also engaging in advocacy efforts.

While organisations have been quick to identify opportunities in PPE production, they are also working to create other livelihood opportunities. SABAH Nepal, for example, has diversified its supply chains to market food items that are dried, pickled, frozen and ready-to-cook. They are also training their members to make liquid soaps and sanitisers. SEWA West Bengal is training homeworkers to become grassroots leaders or agewans. These leaders, the organisation hopes, will improve the effectiveness of government outreach programmes through community monitoring of public distribution schemes and cash transfers.

Organisations in India have also been lobbying with the government to provide food rations to migrant informal workers as well those who don’t have the necessary paperwork but are in need of state-assisted relief. LIE in Bangladesh has participated in a media-based campaign to highlight the situation of homeworkers. The organisation is also lobbying for informal workers to receive extended social protection, income protection and job support. HBWWF has been compiling complaints received from homeworkers and factory workers on the issue of non-payment of wages and has been registering these grievances with the concerned labour department. They have also been advocating for the formulation of a COVID-19 Emergency Ordinance and for Standard Operating Procedures to apply to factories.

An Eye On The Future

While orders from international brands may not be viable in the near future, SABAH Nepal is optimistic that the “future is handmade and the future is natural.” It is investing heavily in its supply chains that produce products made from natural fibres like Himalayan Nettle. And is also encouraging homeworkers – who were previously part of the garment supply chains – to take up work in its food processing and agricultural initiatives. However, the enterprise believes that it will face stiff competition from big market corporate players that are also supplying local food products.

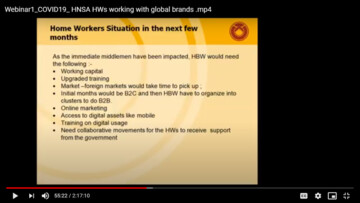

SEWA Bharat, in West Bengal, is optimistic that trainings in digital will help homeworkers connect to online markets. They are also raising funds to provide homeworkers with enough working capital to produce their own products. HBWWF is lobbying to have homeworkers registered under Pakistan’s Social Security Act and for the universalisation of social security.

However, the organisation sees a sharp rise in the informal workforce in the coming years and that this will lead to further economic exploitation.

Workers and organisations are unanimous in their belief that pressure needs to be built on brands to address worker needs and to ensure that they extend social protection to all workers in their supply chains. They also think that it critical for organisations and workers to come together, at this juncture, to build a global campaign that secures the rights of workers and to ensure that their lives are not destroyed by the pandemic.